I stood in front of a still life, arm outstretched with my metal ruler toward the adjacent landscape.

“51 cm,” I whispered to my phone’s Notes app.

A few tourists glanced over as I shuffled sideways, measuring gap after gap between works in MoMA’s galleries.

“Sir, are you planning an art heist?”

The security guard’s voice made me jump, ruler clattering against the wall.

I tried explaining that I was just measuring painting distances, which, in retrospect, sounded exactly like something an art thief would say.

I couldn’t help it. For weeks, the spaces between paintings had been haunting me. Some works huddled close like conspirators, while others stood distant as strangers. What determined their distances? Was there some secret formula to the way they are arranged?

I need to know.

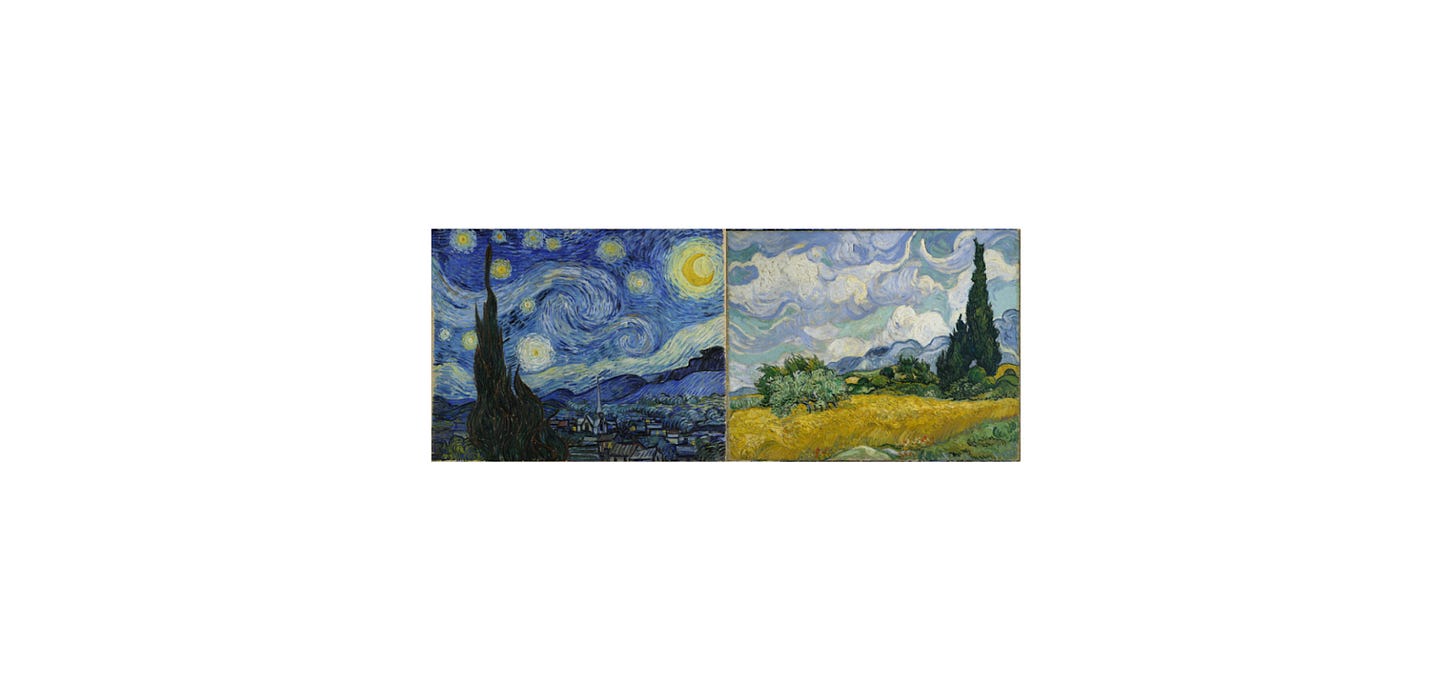

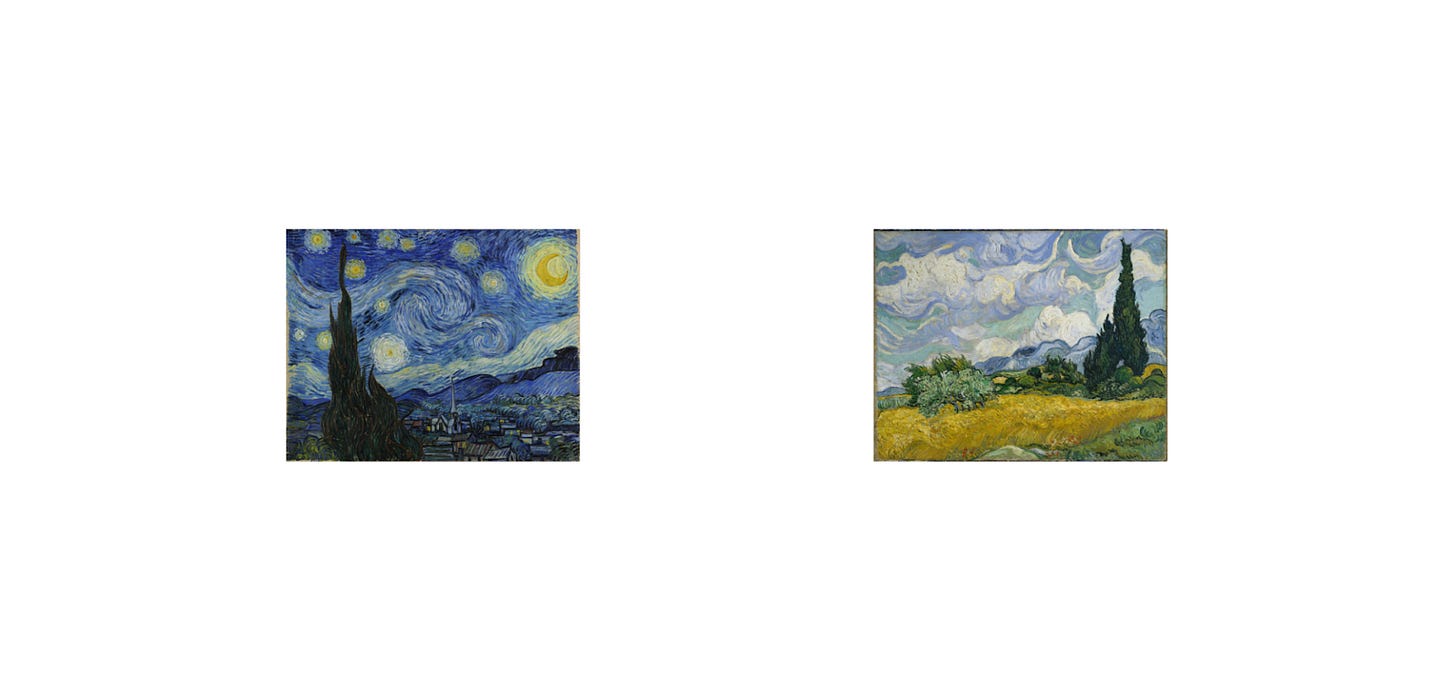

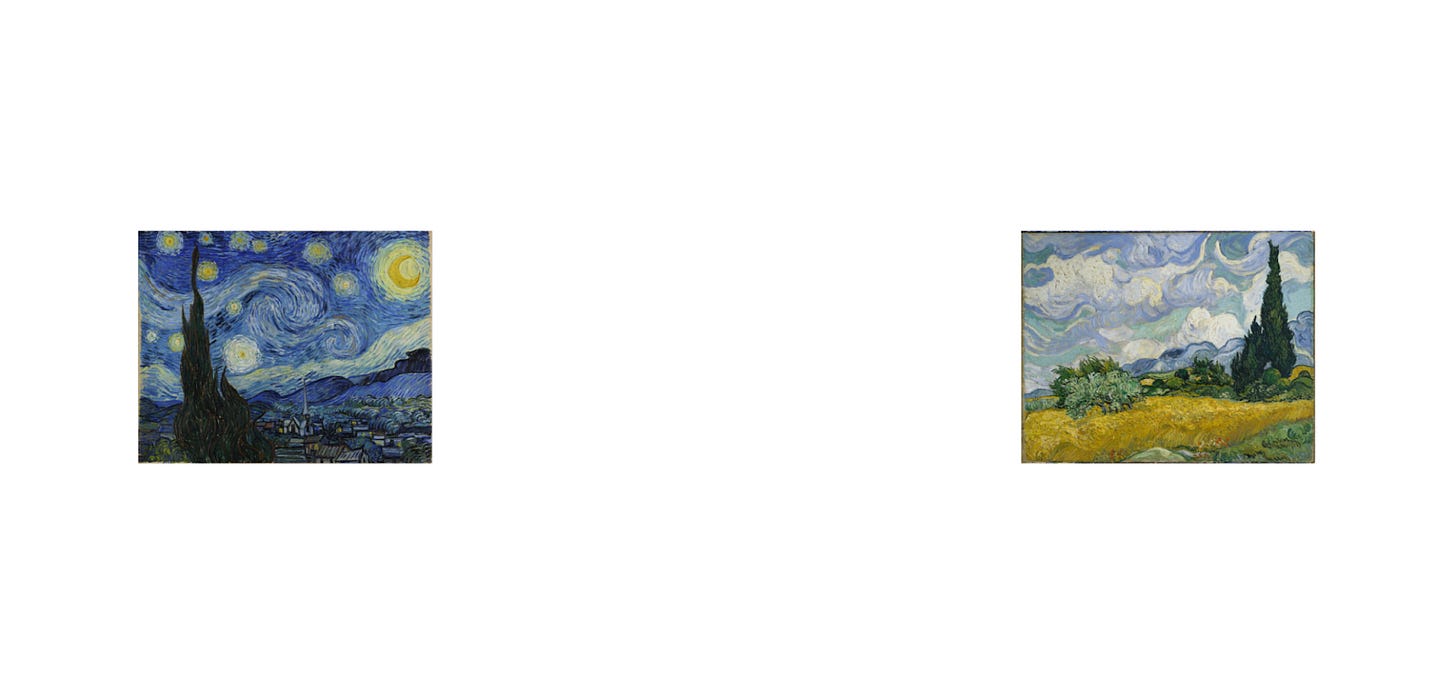

After getting escorted out of MoMA, I did what any reasonable person would do: I opened PowerPoint, and dragged and dropped Van Gogh’s Starry Night and Wheat Field with Cypresses into Slide 1. (I know, I know—using Microsoft Office to rearrange Van Gogh is probably some form of art crime, but lacking a personal collection of Van Goghs and a museum wing to rearrange them in, Microsoft Office would have to do.)

I chose these two paintings deliberately. They’re natural companions, painted in the same year, sharing Van Gogh’s distinctive swirling brush strokes and that deep emotional resonance between sky and earth. By choosing two pieces that clearly belong together, I could focus purely on how distance affects their relationship, rather than wondering if they should be paired at all.

I spent an entire Sunday adjusting digital versions of these masterpieces back and forth. And like any good crime, this digital felony revealed something fascinating.

When placed side by side like a diptych, the paintings created this rushing river of energy. The swirling sky of Starry Night seemed to pour directly into the windswept wheat field, their individual stories dissolved into a single narrative about existence itself. At this distance, you can’t experience one without the other; their energies were completely intertwined.

With one painting-width between them, they fell into a perfect dialogue. Each piece maintained its distinct character while echoing the other’s rhythms—the cypress trees reaching up in both, the celestial swirls above mirroring the earthly currents below. The space between them became a breath between sentences, giving each statement room to resonate before the other responded.

With two widths of space between them, they became like twin stars—each with its own fierce gravity, each commanding its own orbit. The distance highlighted their individual power—Starry Night’s cosmic drama, Wheat Field’s grounded vitality. The space between wasn’t empty—it became a necessary journey, letting you fully leave one reality before entering another. Their relationship wasn't diminished by this distance; instead, it gained a new dimension: the power of how two complete worlds could still be in dialogue.

And space, I was discovering, works this way everywhere. The pattern emerged in every scale: Two skyscrapers standing shoulder to shoulder create one commanding presence; the same towers across a plaza become a frame for the sky between them. Two drum beats close together create momentum; the same beats spaced apart build suspense. Two paragraphs pushed together feel urgent; the same paragraphs spaced apart let each idea sink in.

Buildings. Music. Words. We understand this everywhere.

Yet somehow, when it comes to relationships, we resist. When someone needs a different distance, we treat it as rejection rather than revelation, as if they’re violating some universal law of relationship spacing, as if there's only one way for a heart to speak to a heart.

When I told my then-girlfriend that I could only meet her once a week because of my startup, I saw the hurt in her eyes. We both saw distance as rejection—me guilt-ridden, her seeing it as abandonment.

But looking back now, I understand something I couldn’t see then: my need for space wasn’t about rejection.

Like those paintings in my makeshift museum, each distance in our relationships tells its own story. Sometimes we’re a diptych, our lives flowing into each other like Van Gogh’s sky meeting earth. Sometimes we’re in dialogue, like those cypress trees echoing across space. And sometimes we’re like those distant paintings, each fully ourselves, creating something powerful precisely because we stand apart.

The key isn’t finding the right distance, but developing a taste for how connection transforms across distances.

Maybe that’s the real art crime—not my digital vandalism, but our stubborn insistence on fixed perspectives in a world that reveals its truths to us in so many ways.

Curatorial acknowledgments: , , , , , , , Rita Koon, and Jennifer Scott for their invaluable guidance in arranging these thoughts. To the MoMA security guard, wherever you are—I promise it was for art. And to , my first patron of the arts—this digital gallery exists because of you.

Yes!! This is wonderful. Love love the connection to distance and relationships. Perspective is a wonderful thing.

The framing of images, buildings, opinions and people are oh so important in how we see them.

Great work from my favourite art criminal, turned out beautifuflly.

KZ, you are a thief! Every time I read your posts you steal my attention. No, scratch that. You take my interest captive - and I’m always so pleased when you do. It’s like Stockholm syndrome for readers.

What’s so clever about this piece is how you subtly play with space in the writing itself. Exhibit A: the first 4 lines - two pairs of two lines that are almost perfectly symmetrical. Exhibit B: the two five-line paragraphs that book-end the Van Gogh paintings that you arranged with one painting-width between them - again, pretty much symmetrical.

I also loved your analysis of the two paintings. It’s incredible when you see them together. Or apart. Or slightly further apart. And so beautiful the analogy you draw with human relationships. Perhaps in our keenness to experience our energy completely intertwining with someone else’s, we can forget the value of entering into balanced dialogue, of our distinct characters echoing each other’s rhythms, or simply standing as two individuals in command of our own orbits.

Looking forward to reading this piece’s twin star.